Pope Francis, Gossip, and the Long History of the “Sins of the Tongue”

Titivillus (upper right), the demon responsible for scribal error and collecting idle talk, is thwarted by the Virgin of Mercy. Diego de la Cruz (c. 1485), Burgos, Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas.

Pope Francis on the Plague of Gossip

At the Angelus prayer delivered above St. Peter’s Square on Sunday, September 6, Pope Francis strayed from his planned remarks and declared gossiping a worse plague than COVID-19. In his address, commenting on Matthew 18:15-20, the pope announced that “today’s passage speaks about fraternal correction, and invites us to reflect on the twofold dimension of Christian existence: community, which demands safeguarding communion - that is, the unity of the Church - and personal, which obliges attention and respect for every individual conscience” (Pope Francis, Angelus, Sept. 6, 2020). While discussing the proper method for correction (at the individual and communal levels) Pope Francis warned about the dangers of gossip:

“When we see a mistake, a fault, a slip, in that brother or sister, usually the first thing we do is to go and recount it to others, to gossip. And gossip closes the heart to the community, closes off the unity of the Church. The great gossiper is the devil, who always goes about telling bad things about others, because he is the liar who seeks to separate the Church to distance brothers and sisters and not create community. Please, brothers and sisters, let us make an effort not to gossip. Chatter is a plague more awful than Covid! Let us make an effort: no gossip. It is the love of Jesus, who had embraced the tax collectors and Gentiles, scandalizing the conformists of the time. However it is not a sentence without an appeal, but a recognition that at times our human attempts may fail, and that only being before God can bring the brother to face his own conscience and responsibility for his actions. If this matter does not work, then silence and prayer for the brother or sister who has made a mistake, but never gossip.”

Whether or not the pontiff had something specific on his mind is unclear — though many could certainly make informed guesses as to what he is referencing — but this is not the first time he has spoken out against gossip. In 2018 Pope Francis proclaimed that the “tongue kills like a knife” and in 2016 he reminded nuns and priests that they had a responsibility to prevent “the terrorism of gossip.”

Pope Francis’s concern for the destructive power of gossip within communities is part of a long tradition (though using varying terminology such as idle speech, murmuring, chattering, detraction, backbiting, etc.) which stretches back to the sapiential and prophetic books, various epistles in the New Testament, the Patristic period, and the explosion of treatises on the “sins of the tongue” in the Middle Ages. What follows is not an exhaustive account of clerical concern about ungoverned tongues, but highlights a number of important developments in the tradition.

Evil Tongues in the Bible

Several books of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament convey anxiety over the injurious potential and deadly consequences of evil or unguarded tongues and remind the righteous to keep sin from their lips.

In the Book of Job we learn that evil is both sweet in the mouth and hidden under the tongue (20:12) and of the folly of words uttered into the wind (6:26). In the Book of Psalms the tongue hides labor and sorrow (Psalms 9:28); the tongue is compared to a sharp razor and a sword (Psalms 51:4; 56:5). The Book of Proverbs suggests that both “death and life are in the power of the tongue” (18:21) and that “he that keepeth his mouth and his tongue, keepeth his soul from distress” (21:23). The Book of Wisdom identifies more specific sins associated with the tongue: “Keep yourselves therefore from murmuring, which profiteth nothing, and refrain your tongue from detraction, for an obscure speech shall not go for nought: and the mouth that belieth, killeth the soul” (1:11). That the tongue has the potential to kill is reiterated in Ecclesiasticus (Sirach): “Many have fallen by the edge of the sword, but not so many as have perished by their own tongue” (28:22). The tongue is likened to a piercing arrow in the book of the Prophet Jeremiah because it speaks peace while secretly enacting evil (9:8).

Concerns over wicked tongues and the proper governance of speech is not unique to the Hebrew Bible, of course. In his epistle (particularly in the third chapter), James speaks at length of the dangerous consequences of an unbridled tongue. The tongue can be not only injurious to others, it places the user in mortal danger as well: “And if any man think himself to be religious, not bridling his tongue, but deceiving his own heart, this man's religion is vain” (1:26). Though “the tongue is indeed a little member, and boasteth great things. Behold how small a fire kindleth a great wood. And the tongue is a fire, a world of iniquity. The tongue is placed among our members, which defileth the whole body, and inflameth the wheel of our nativity, being set on fire by hell” (3:5-6). James, too, offers insight into the specific evils of the tongue he has in mind: “Detract not one another, my brethren. He that detracteth his brother, or he that judgeth his brother, detracteth the law, and judgeth the law. But if thou judge the law, thou art not a doer of the law, but a judge” (4:11). The similarity between James’s epistle and Pope Francis’s reminder to the Church is clear. The Apostle Paul, in the opening to his epistle to the Romans, also has harsh words for detractors who are “hateful to God” (1:30). Lest the mortal danger of loose tongues be misunderstood, the Gospel of Matthew reminds: “But I say unto you, that every idle word that men shall speak, they shall render an account for it in the day of judgment” (12:36).

These passages are just a small sampling of the Bible’s obvious interest in the hazardous potential of the tongue. In the Patristic period and throughout the Middle Ages and beyond expression of these concerns becomes so universal that the “sins of the tongue” are categorized within or alongside the conceptualizations of the seven deadly sins and are regular subjects for sermons and exempla.

The Ungoverned Tongue in the Writings of the Patristics and the Early Middle Ages

The theologians of the Patristic period and early Middle Ages took on the task of writing commentaries on scriptural passages such as those given above. The Book of Wisdom’s warning against murmuring and detraction is among the many scriptural verses explicated by St. Augustine in his late-fourth-century text De mendacio (On Lying). The subject of deception preoccupied Augustine; he wrote a second treatise (Contra mendacium) on the subject around 25 years after completing De mendacio. According to Augustine, “in general when the Scripture speaks of the mouth, it signifies the very seat of our conception in the heart” (De mendacio, ¶ 31). The Book of Wisdom warns that backbiting and murmurings slays the soul, Augustine explains, because, though it is done in secret, it is clear to the ears of God (De mendacio, ¶ 31). Augustine continues: “Now this detraction takes place through malevolence, when any man not only with mouth and voice of the body does utter what he forges against any, but even without speaking wishes him to be thought such; which is in truth to detract with the mouth of the heart; which thing, it says, cannot be obscured and hidden from God” (De mendacio, ¶ 32).

Pope Gregory I (the Great, d. 604), in his commentary on the Book of Job (Moralia in Iob) speaks at length of the sins associated with speech and in particular about idle words. In his explanation of chapter 6, Gregory observes that there are two types of speech “which are very troublesome and mischievous to mankind, the one which aims to commend even forward things, the other which studies to be always carping even at right ones. The one is carried downward with the stream, the other sets itself to close the very channels and streams of truth. Fear keeps down the one, pride sets up the other” (Moralia in Iob, Book VII, ¶ 57). Gregory then shifts to interpreting the reference in Job 6:26 to words spoken into the wind. Here, he incorporates several scriptural passages which address idle talk and evil tongues. He offers definitions, explanations, and insight into the far-reaching consequences of unguarded tongues:

“But he proceeded to make known whence it is that men come even to the effrontery of unjust upbraiding, when he added, And ye speak words to the wind. For to ‘speak, words to the wind’ is to talk idly. For often when the tongue is not withheld from idle words, a loose is even given to the rashness of foolish reviling. For it is by certain steps of its descent, that the slothful soul is driven into the pitfall. Thus while we neglect to guard against idle words, we are brought to mischievous ones, so that it first gives satisfaction to speak of the concerns of others, and afterwards the tongue by detraction carps at the life of those of whom it speaks, and sometimes even breaks out into open revilings. Hence the incitements are sown of angry passions, jars arise, the fire-brands of animosity are kindled, peace is altogether extinguished in men's hearts. Hence it is well said by Solomon, He that letteth out water is a beginning of brawls. [Prov. 17, 14] For to let out water is to let the tongue loose in a flood of words, contrary to which he at the same time declares in a favourable sense, saying, The words of a man's mouth are as deep waters. [Prov. 18, 4] He then that letteth out water is a beginning of brawls, for he who neglects to refrain his tongue, dissipates concord. Hence it is written contrariwise, He that silenceth a fool, softeneth wrath. [Prov. 26, 10. Vulg.] But that everyone that is given to much talking cannot maintain the straight path of righteousness, the Prophet testifies, in that he saith, For an evil speaker shall not be led right upon the earth. [Ps. 140, 11] Hence again Solomon saith, In the multitude of words there wanteth not sin. [Prov. 10, 19] Hence Isaiah saith, And the cultivation of righteousness, silence; so pointing out that the righteousness of the interior is desolated, when we do not withhold from immoderate talking. Hence James saith, If any man among you think himself to be religious, and bridleth not his tongue, but deceiveth his own heart, this man's religion is vain. [James 1, 26] Hence he says again, Let every man be swift to hear, slow to speak. [1, 19] Hence he adds again, The tongue is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison. [3, 8] Hence ‘Truth’ warns us by his own lips, saying, Every idle word that men shall speak, they shall give account thereof in the day of judgment. [Matt. 12, 36] For an idle word is such as lacks either cause of just occasion, or purpose of kind serviceableness. If then an account is demanded for idle speech, it is very deeply to be considered what punishment followeth after that much talking, wherein we sin even by words of pride” (Moralia in Iob, Book VII, ¶ 57, 58).

One final development in the period that should be mentioned is to be found in the enormously popular apocryphal work Visio Pauli, which claim’s to be an account of the Apostle Paul’s journey to the mysterious third heaven (2 Corinthians 12) and adds a visit to the pits of hell.

Visio Pauli. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 020, 62v (c. 1300-25).

The Visio Pauli is among the earliest texts to enumerate specific torments for those who sin by means of the tongue (a tradition we find continued in Dante’s Inferno). Some version of the Visio Pauli likely originated in third century Egypt; Greek versions followed in the fifth and sixth centuries as did Latin translations based on the Greek. The most popular Latin text, which relates Paul’s tour through hell only, is likely a ninth-century composition (on the Visio Pauli, see Bullitta). An angel of God first brings Paul to the heavens to witness the bliss awaiting the righteous. Paul is also shown torments in the pits of hell. In the abyss of hell Paul observes a fiery river in which some are submerged up to their knees, some to the navel, others up to the lips, and some up to the hair. Paul asks his angel guide: “Who are these, sir, immersed up to their knees in fire?” (trans. James, in Elliott p. 633). The angel responds:

“These are they who when they have gone out of church occupy themselves with idle disputes. Those who are immersed up to the navel are those who, when they have taken the body and blood of Christ, go and fornicate and do not cease from their sins till they die. Those who are immersed up to the lips are those who slander each other when they assemble in the church of God; those up to the eyebrows are those who nod to each other and plot spite against their neighbour.” (trans. James, in Elliott, p. 633).

Here we find specific torments meted out to those who sin with their tongues and detract their neighbors in secrecy. Elsewhere in hell Paul witnesses sinners whose tongues and lips are sliced away by fiery razors or who perpetually gnaw at their own tongues because the tongue has been the source of their damnation. This imagery and focus on the sins of the tongue would later become increasingly popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and indeed we can see its influence on a variety of works, including Dante’s Inferno.

Pastoral Care and the Sins of the Tongue in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries

At the end of the Fourth Lateran Council, convened by Pope Innocent III in 1215, seventy-one constitutions had been compiled on subjects ranging from church reform, programs for pastoral care that sought to more-heavily involve parishioners in their own Christian learning and salvation, and announcements on a new crusade to the Holy Land and on Jewish-Christian relations. The reforms and recommendations for pastoral care were adopted and implemented throughout Western Europe, and in the decades that followed, new theological and penitential manuals meant to aid the program and preachers implementing it were composed, disseminated, and later translated. Similar councils and constitutions were produced at the local level, like the Lambeth Constitutions of 1281 (associated with the leadership of John Peckham, Archbishop of Canterbury 1272-1292) which required priests to (at least four times per year) teach and explain the Articles of the Faith, the Ten Commandments, the Works of Mercy, the Seven Virtues and Sacraments, and — more importantly for the present discussion — the seven deadly sins. The proliferation of manuals addressing the seven deadly sins reveals both their importance within the church’s program of reform and pastoral care and their popularity with clerics and other listeners or readers.

Some of these treatises on the seven deadly sins (on the genre, see Newhauser, 1993), like the immensely popular Summa de vitiis compiled by the Dominican William Peraldus (d. 1271), paid special attention to the sins of the tongue. Peraldus’s treatise on the vices is attested in approximately 500 manuscript copies (see Richard Newhauser’s overview of the Summa and brief introduction to the text).

An Illustration from Peraldus’s Summa de virtutibus et vitiis. A Knight prepares for battle against the seven deadly sins. The shield of the trinity protects him. British Library, Harley MS 3244, folios 27-28 (c. 1255-65).

Peraldus outlines twenty-four sins of the tongue:

1. Blasphemy 2. Murmuring 3. Excusing one's sin. 4. Perjury. 5. Lying. 6. Backbiting (detractio). 7. Flattery. 8. Cursing. 9. Insult. 10. Contentiousness. 11. Derision. 12. Wicked counsel. 13. Sowing discord. 14. Being double-tongued, hypocrisy. 15. Rumor-mongering. 16. Boasting. 17. Tattling. 18. Indiscreet threats. 19. Indiscreet promises. 20. Idle speech. 21. Gabbling (multiloquium). 22. Dirty talk (turpiloquium). 23. Loose talk and facetiousness (scurrilitas). 24. Indiscreet silence, sullenness (Richard Newhauser).

Among the eight remedies suggested for addressing these sins of the tongue is the silence of the cloister. Several of these sins of the tongue can be connected to the gossip and to the kind of consequences Pope Francis appears to be be wary of in the context of the religious community.

The influential Dominican Doctor the Church St. Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) also addressed the sins of the tongue and the pernicious nature of backbiting in particular in his Summa theologiae. Backbiting (detractio) is discussed in the “Second Part of the Second Part” in a section on verbal injuries.

During the second half of the thirteenth and throughout the fourteenth treatises on the seven deadly sins (and the sins of the tongue) were widely disseminated in Latin copies and in translations into a variety of European vernaculars (for a bibliography of texts, see Newhauser, 1993). The lessons on the sins were also adapted into sermons, exempla, instructional manuals for nobility, as well as other types of literature and media.

Many of these texts dwelt in particular on categorizing and then offering examples of the sins of the tongue as well as enumerating the punishments (like the Visio Pauli before them) meted out to those who traffic in idle talk or detract their neighbors.

As Susan E. Phillips has shown, idle speech/gossip came to encompass “a range of verbal transgressions” that included “excessive chatter, impudent and unproductive speech, tale-telling, news, disturbing reports, bawdy jokes, lies, and scorning one’s neighbor” (p. 6). All of these verbal transgressions would be recorded and all would have to account for them at Judgment Day.

For example, the Gilbertine monk Robert Mannyng of Brunne, in his early fourteenth-century manual Handlyng Synne (a translation of the late thirteenth-century Anglo-Norman work Manuel des pechiez), includes in his section on the sin of pride an exemplum that tells of the eternal torment endured by a backbiting monk. Mannyng relates a story of a monk who was accustomed to say wicked things behind the backs of his brethren (“felaws”). This backbiter later becomes sick and dies. One night, when the monastery has finished praying at Matins, one brother remains behind in the chapel. He is confronted with the grisly sight of the deceased backbiting monk and watches as the backbiter gnaws his “brennynge” (burning) tongue “al to pecys” (all to pieces). The sinning monk then speaks to his former brother: “y was a wykked bakbytere…Þe wykked wurdys þat y haue seyd, wykkedly are þey on me leyde” (I was a wicked backbiter…the wicked words that I have said are now wickedly laid upon me). The backbiter refers to the Gospels to remind his brother, and the audience, of the torments awaiting those who sin through their tongues: “Yn þe byble men mow se, yn a boke of pryvuyte, Apocalypse þyse clerkys wote, Seynt Ioun þe euangylyst hyt wrote; Oure lorde seyþ þat þey shal ete here tunges in peynes, and al to-frete, þese lyers and þeses bakbyters; þe tale, of þys, wytnes berys” (In the Bible men may see, in a book of secret things, called Apocalypse among clerks, which Saint John the Evangelist wrote; our lord says that they shall eat there tongues in pain, and eat it all up, these liars and backbiters. This tale bears witness to that.”

In the fourteenth-century Middle English treatise The Book of Vices and Virtues (a translation of the Somme le roi written by Laurent d'Orléans in the late-thirteenth century for the children of Philip III of France), the sins of the mouth and tongue are classified within the branch of gluttony. The compiler of The Book of Vices and Virtues admits that it is difficult to enumerate (“noumbre”) “alle þe synnes þat comeþ of wikkede tonges” (all the sins that come from wicked tongues), but ten in particular are identified: idle speech (ydel), boasting (auauntyng), deceitful flattery (losengerie), backbiting (bakbityng), lying (lesynges), forswearing (forswerynges), quarreling (stryuynges), complaining or murmuring (grucchynges), rebelling or disobedience (rebellynges), and blasphemy (blasphemye). This list is followed by definitions of each type of sinful speech and examples meant to further illuminate them. The backbiter is likened to the scorpion who makes a good impression on its face but poisons with its tail. The author is not sparing of words to treat idle speech (gossip). Gossip is never idle, despite its name. It is full of harm and perilous (“ful of harm and wel perilous”) and voids the heart of all goodness. Idle speech is also collected and judged by God, the author warns.

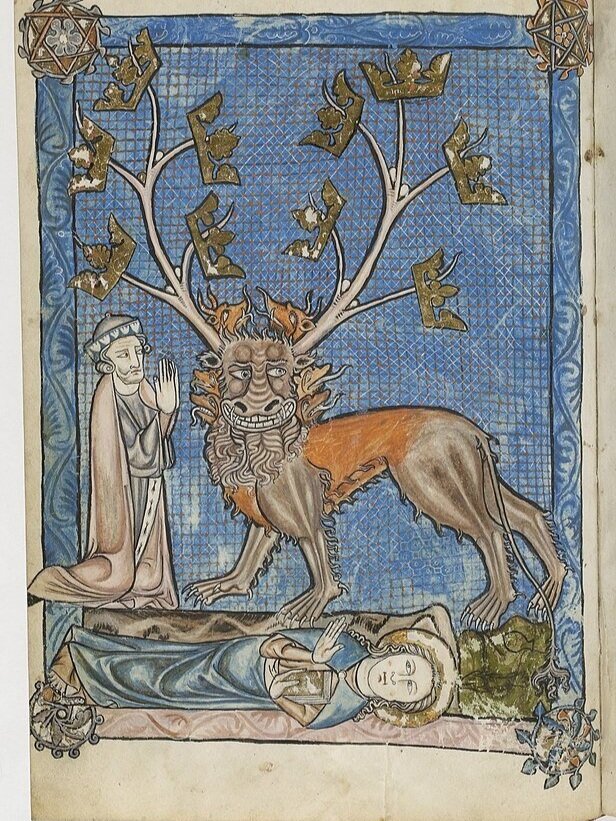

Somme le roi, the seven-headed beast with ten crowns (the Apocalypse of John), 1294. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Français 938 Fol.8v.

There are a couple of important points to note here. First, the sins of the tongue could be classified by themselves, or, as we see in these two examples, within one or the other branches of the traditional seven deadly sins. Second, the fact that Mannyng, and his source the Manuel des pechiez of William Waddington, focus on the backbiting of a monk is significant and helps us better understand the long history of ecclesiastical concern over gossip and detraction within the monastic community.

Susan Phillips has summed up the effect the Church’s efforts to police idle speech had on one local intellectual climate in her book Transforming Talk: The Problem with Gossip in Late Medieval England:

“Gossips beware. The literature of late medieval England abounds with cautionary tales concerning the dangers of idle talk. Whether in penitential manuals, courtesy books, or literary compilations, English writers repeatedly tell the story of gossip’s ‘euele werke,’ revealing the dire consequences facing anyone who engages in unproductive speech. On the pages of moralizing texts, industrious devils record idle words in their account books, while uncompromising authorities sever wagging tongues and place gossiping bodies on ignominious public display” (p. 1).

The thirteenth- and fourteenth-century church’s pastoral efforts to regularly remind parishioners of the dangers of sin was so successful that the imagery utilized in treatises on the seven deadly sins and sins of the tongue came to be incorporated into the popular literature and legends of the period as well. The figure of Envye in William Langland’s Piers Plowman is clearly a backbiter, and wields an “addres tonge” that spits poison. In the eighth circle of Hell (the cavern Malebolge) in Dante’s Inferno, we find deceivers doomed to speaking with tongues of flame. In the Ulysses episode in Canto 26, we also find the imagery from the epistle of James noted above (see Bates and Rendall). The figure of the backbiter is also mentioned in the “Parson’s Tale” in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and idle talk, detraction, and gossip are regular features in the tales of other pilgrims (think also of the “Manciple’s Tale”). This period also witnessed the popularization of a particular demon, Titivillus, who was associated with scribal error and with the collecting of idle talk to be utilized in the judgment of sinners.

The Wicked Tongue as Plague and Source of Strife, War, and Other Calamities

In the sixteenth century and seventeenth centuries, during an era of religious transformation and reform in Western Europe, gossip and detraction continued to be of concern in the monastery — especially as accusations of heresy were regularly levied — but also for the negative effects gossip could have on governance and the ways in which it could lead to conflict. For the case of England, studies by Susan E. Phillips, Sandy Bardsley, David Cressy, and Carla Mazzio as well as editions of texts, like Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin’s edition of three treatises (A Treatise of the Good and Evell Tounge, A Direction for the Government of the Tongue according to Gods worde, The Araignement of an unruly Tongue), have illuminated the changing nature of thinking about idle and backbiting speech in the late medieval and early modern periods.

In his work on conceptions of evil tongues in early modern England, David Cressy observes that “spokesmen for the established order blamed misuse of mankind’s vocal gift for dissension in families, division in churches, and turmoil in the state. The tongue was the instrument of voice, voice the medium of speech, speech the utterance of meaning, and words the elements that gave language its benign or malignant power. All were double-edged instruments, both beneficial and damaging to society” (Dangerous Talk, pp. 1-2). The tongue was not just a detriment to personal morality and salvation, it threatened the entire social fabric. The tongue also came to be seen as a vector for the spread of disease, both literal sickness and figurative plagues on social harmony (see Mazzio, 1998).

The Evil Tongue in George Wither’s Collection of Emblemes (1635).

The great philosopher, and biblical scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam is among the more prominent thinkers to take up the subject of the loose tongue as spreader of social sickness. In his treatise on the tongue, De linguae usu atque abusu, liber utilissimus (c. 1525), Erasmus argues that just as the tongue can indicate illness to doctors, the tongue too can reveal the health or sickness of the mind of the person wielding it (see Mazzio, 1997). When Erasmus wrote Lingua he had for some time been suffering through a haze of rumors and detraction.

Margaret Mann Phillips offers a concise summary of the context of Erasmus’ Lingua and the dedicatory letter prefacing the text:

“The dedicatory letter dwelt on the central subject of the book by asking the question: which are the more harmful, diseases of the body or diseases of the mind? Certainly, says Erasmus, diseases of the mind, and particularly those which are unnoticed by those who suffer from them. We diagnose physical ailments with the mind, but what faculty have we to diagnose our mental ills? Bodily plagues are regional (thirty years ago, he says, England did not know the sweating sickness, and it never crossed the frontiers). They attack only certain parts of the body; mental illness affects the whole personality and knows no boundaries. What is the worst physical disease? Erasmus as a man of his time replies syphilis, the pox. Which is the worst disease of the mind? An unbridled tongue. This disease is not new. It crops up now here, now there. This fatal contagion has now taken over the whole world; in the courts of princes, in private homes, in the schools of theology, in the monasteries, in the barracks and the labourers' cottages. No one seems able to cure it, and those who try (like inexperienced physicians) only make it worse. Mindful of his correspondent, Erasmus prudently says it is for bishops learned in the Gospel and moderate in mind, to do this. ‘I have no authority,’ he says, ‘no erudition, no prudence equal to this task, but I offer a little medicine, which if it cannot cure at least assuage’” (114-114).

Erasmus is adamant that detraction and gossip are not only personally injurious; loose tongues are destructive to all communities. Foolish murmuring can cause war and public strife. While Erasmus is anxious over the destructive social role of idle speech, he spends most of his treatise on the backbiting and murmuring infecting the monastic community; this is a concern clearly inherited, via long tradition, by Pope Francis.

A Continuous Tradition

In 1870, a Fr. Bélet of the Diocese of Basel published a treatise on backbiting (originally in French) that synthesizes the thousands of years of tradition briefly sketched above and shows a continuous line of admonitions concerning the pernicious effects of idle and/or backbiting tongues. In his short treatise Fr. Bélet refers to key figures of the classical world (Aristotle, Plato, Seneca, Horace, Pliny), to scripture (the Psalms, Proverbs, Isaiah, the epistle of James, the Gospels, the epistles of Paul), and to well-known theologians (John Chrysostom, Jerome, Cassian, Gregory the Great, Augustine, Bernard of Clairvaux, St. Francis of Assisi, Bonaventure, William Peraldus, and Thomas Aquinas).

Fr. Bélet offers a definition of backbiting (based on Aquinas), lists eight ways that people commonly backbite their neighbors, and speculates as to why humanity has a propensity for disparaging speech. Backbiters are, Bélet laments, everywhere: “Like gnats, backbiters' words have spread throughout the land and infested every class of society, both sexes, every age and condition, rich and poor, servants and masters alike. Many men are not blasphemers, but few — hardly any — do not backbite.”

The backbiter kindles fires that are all-consuming. The backbiter is likened to a dog, a sea urchin, a beetle, a leech, the wash basin of the devil (Peraldus), a hog, a lion, a hyena, a counterfeiter or thief, and, most appropriately, a serpent. Fr. Bélet further suggests that the tongue of the backbiter fires three arrows and slays the gossiper, the listener, and the victim. Indeed, in Bélet’s treatise the listener encourages the gossip and promotes further loose speech, and thus is as guilty as the backbiter.

For Fr. Bélet, the most destructive and lasting consequences of venomous tongues are to the reputations (“what is most precious”) of the targets of murmuring and detraction. He continues:

“It is a common principle among theologians that restoring their neighbor's reputation is obligatory not only for those who have revealed an imaginary crime of his, but also those who have revealed a true but secret crime. They are held to giving him at least an equivalent compensation: and they owe this compensation to the detriment not only of their own reputation, but also their life. Along with their neighbor's reputation, they must repair all the harm he has incurred; and they must do so even if what they revealed is true. Since the thing is true, they are held to tell everyone who heard them not that they were lying, but that they were backbiting.”

What appears to most disturbing to Bélet, like Pope Francis, is the revelation of hidden or unknown faults — whether real or imagined — through rumor and idle chatter. The hidden faults are known to God, and should be dealt with between neighbors, Bélet claims, rather than publicly through murmuring.

Critical Theory on the Social Role of Gossip

While the Church’s position on idle talk that leads to backbiting has always been manifestly clear, modern scholarship on the theory of gossip has attempted to complicate our understanding of its social function.

The noun gossip comes down from Old English (god-sibb). It originally meant sibling in God or related in God and could denote a godparent/sponsor at baptism. Later, the term came to include any close friend who could be chosen as a godparent. As Patricia Meyer Spacks observes in her book Gossip, the word’s meaning then degraded over time (see chapter two, on gossip’s reputation, in particular).

In her book Transformative Talk Susan E. Phillips provides a helpful introductory summary to contemporary gossip theory:

“In recent decades, scholars have endeavored to explicate gossip’s work. While early theorists focused on the destructive qualities of idle talk, providing epidemiological models for this discursive ‘virus,’ more recently the discussion has turned to the vital social role that gossip plays. Two competing models have predominated in gossip theory. The first, largely espoused by anthropologists, identifies gossip as an instrument of social control. Idle talk, the theory argues, both establishes membership in a community and polices that community’s morals. In certain groups, gossip acts as a feared social regulator, enforcing standards of behavior and promoting competition through its approval and disapproval. Critiquing the model of social control, sociologists and social psychologists have focused on the ways in which gossip serves the individuals engaged in it. The second model defines idle talk as a ‘social exchange,’ in which information is traded for status, money, and services. The last decade has seen a reformulation of these two methodological extremes, as gossip theorists across several disciplines have sought models that combine social and individual perspectives” (pp. 3-4).

Gossip, then, can be transgressive. It can be interpreted “as a mode of resistance, a subversive speech that ‘will not be suppressed’” (p. 5). Gossip can also help individuals “establish and maintain social bonds” within ever-expanding social networks.

Whether Pope Francis had something specific in mind, or not, when he spoke out against gossip (again) during the Angelus prayer will likely remain a mystery. We can also ask what kind of gossip the Pope is warning against. Does he have in mind backbiting speech which threatens reputations and slays the speaker, the listener, and the victim all at once? Is he thinking of individual reputations or the Church’s reputation as a community? Is he referring to the public airing of the Church’s many transgressions and failures in addressing wrongdoing? Is Pope Francis adding his voice to the very long tradition preoccupied with the sins of the tongue and idle speech’s supposed capacity for social destruction? Or is the pontiff an authority railing against subversive speech that threatens his, or the institution’s, power?

Further Reading:

Bardsley, Sandy. Venomous Tongues: Speech and Gender in Late Medieval England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Bates, Richard and Thomas Rendall. “Dante’s Ulysses and the Epistle of James.” Dante Studies 107 (1989), 33-44.

Bullitta, Dario, ed. and trans. Páls Leizla: The Vision of St Paul. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 2017.

Carrington, Laurel. “Erasmus’ Lingua: The Double-Edged Tongue.” Erasmus Studies 9.1 (1989), 106-118.

Cawsey, Kathy. Images of Language in Middle English Vernacular Writings. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2020.

Craun, Edwin D. Lies, Slander, and Obscenity in Medieval English Literature: Pastoral Rhetoric and the Deviant Speaker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Craun, Edwin D., ed. The Hands of the Tongue: Essays on Deviant Speech. Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2007.

Cressy, David. Dangerous Talk: Scandalous, Seditious, and Treasonable Speech in Pre-Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Denery II, Dallas G. “Biblical Liars and Thirteenth-Century Theologians,” in Richard Newhauser, ed. The Seven Deadly Sins: From Communities to Individuals. Leiden: Brill, 2007, 111-128.

Elliott, J.K.The Apocryphal New Testament. trans. M.R. James. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Ferrante, Joan M. “The Relation of Speech to Sin in the Inferno.” Dante Studies 87 (1969), 33-46.

Godsall-Myers, Jean, ed. Speaking in the Medieval World. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Hayes, Douglas W. “Backbiter and the Rhetoric of Detraction.” Comparative Drama 34.1 (Spring 2000), 53-78.

Hermanowicz, Erika T. “Augustine on Lying.” Speculum 93.3 (July 2018), 699-727.

Jennings, Margaret. “Tutivillus: The Literary Career of the Recording Demon.” Studies in Philology 74.5 (December, 1977).

Carla Mazzio. “Sins of the Tongue,” in David Hillman and Carla Mazzio, eds. The Body in Parts: Fantasies of Corporeality in Early Modern Europe. NY and London: Routledge, 1997, 53-80.

Mazzio, Carla. “Sins of the Tongue in Early Modern England.” Modern Language Studies 28.3-4 (Fall 1998), 95-124.

Newhauser, Richard. The Treatise on Vices and Virtues in Latin and the Vernacular. Turnhout: Brepols, 1993.

Pascua, Esther. “Invisible Enemies: The Devastating Effect of Gossip in Castile at the End of the Fifteenth Century.” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 11.2 (2019), 250-274.

Phillips, Margaret Mann. “Erasmus on the Tongue.” Erasmus Studies 1.1 (1981), 113-125.

Phillips, Susan E. “Gossip and (Un)Official Writing,” in Paul Strohm, ed. Oxford Twenty-First Approaches to Literature: Middle English. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2007, 476-490.

Phillips, Susan E. Transforming Talk: The Problem with Gossip in Late Medieval England. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2007.

Spacks, Patricia Meyer. Gossip. NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

Veldhuizen, Martine. Sins of the Tongue in the Medieval West: Sinful, Unethical, and Criminal Words in Middle Dutch (1300-1550). Turnhout: Brepols, 2017.

Veldhuizen, Martine. “‘Tong breect been’: The Sins of the Tongue in Middle Dutch Religious Didactic Writings.” Journal of Dutch Literature 6.2 (2015), 59-71.

Vienne-Guerrin, Nathalie, ed. The Unruly Tongue in Early Modern England: Three Treatises. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2012.